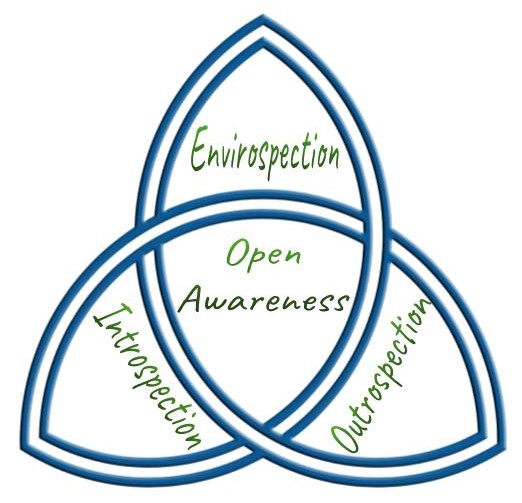

Open Awareness (OA) is an expansive perception that promotes a resourceful state and the following qualities:

- Introspection – metacognitive awareness in which we can mindfully observe mental activities, emotions and somatic experience

- Outrospection – heightened awareness of others and the ways that we relate to them, which cultivates empathy and compassion

- Envirospection – broad awareness of the space around us which connects us to everything in the environment and the cosmos

Applied OA is naturally eco-logical – beneficial for you, others, and the world (win-win-win).

Spacebook provides the means for kids, teenagers and adults to learn and integrate OA into their lives.

Visit the Spacebook resources in the following three categories to access free open awareness recordings:

Realizing how deeply interconnected we all are is the answer!

Joy, creativity, awe, gratitude, compassion, kindness—the qualities we cherish the most will naturally emerge when we drop beneath the illusion of separateness and realize our profound interconnection.

– Dr Dan Siegel, Psychiatry and Paediatric Specialist –

Open Awareness dissolves the illusion of separateness and promotes a sense of interconnection.

Open Awareness article

by Jevon Dangeli, MSc Transpersonal Psychology

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

– Albert Einstein –

Abstract

In this article I will introduce the skill and practice of open awareness, outlining the phenomenology that is associated with this distinct state and mode of perception. I will describe how it can be used to counteract the serious issues that are associated with its counterpart, tunnel awareness, which is always present in the trigger events that lead to stress, anxiety, performance issues and burnout. The essay will also address how open awareness skills can help to resolve the escalating problems that are associated with excessive use of mobile digital media devices, resulting in a generation of digital zombies.

Introduction

A majority of my clients (in coaching and therapy) have suffered from the symptoms of stress, anxiety and burnout. In listening to how these clients have described their personal issues I consistently detected a particular pattern that was almost always present. After a careful and long-term assessment, investigating cases since 2004, I established that this pattern played a crucial role in how these individuals were being negatively affected. The discovery was that at the onset of this pattern, its very trigger, involved a particular mode of perception in which these individuals had become completely focused with their attention on something unpleasant in the situation or on a predominant symptom. This focus was always narrowly fixated, thus these individuals were usually unaware of what else was possible or achievable in those situations. Even if they were aware of other possibilities, their locked in ways of approaching the situation prevented them from establishing more resourceful perceptions and responses. In one sense, their problems arose because of tunnel awareness and remained problems largely because of this limited frame of reference.

Through learning how to open the aperture of their awareness, and integrate this broader perspective, these individuals have (to varying degrees) been able to shift their perception of themselves in relation to the challenging situation or symptom. This was brought about through the establishment of a more expanded sense of self from where the issue could be seen and approached from a more holistic perspective. The experimental process that I used in these sessions (which has become the open awareness technique) included guiding the client to embody their broader perspective, and from that expanded as well as interconnected sense of self, address the situation or symptom more mindfully and resourcefully. At very least, these individuals have experienced a positive and sustainable change. Healing and transformation have been frequent outcomes.

Over the past several years, clients of mine and of other open awareness facilitators, have reported that open awareness not only enables them to deal with stressful situations more resourcefully, but they are able to establish a calm and mindful state with relative ease, as well as sleep better, concentrate for longer, overcome mental blocks and improve performance. Additionally, through becoming less identified with a limiting self-concept, they are less controlled by negative thoughts and reactions. Those who have integrated open awareness through practising it regularly have told me that they feel a deep sense of connection with other individuals. Some speak of an enhanced connection with nature and the spiritual realm, while others refer more to a sense of oneness in which there is no real separation between self and other (or between subject and object). With this comes inner peace and meaning in life.

The history of open awareness

Open awareness is a particular mode of perception in which individuals are attentive to both their own thoughts and feelings as well as those of others, including the context that connects them. It is a type of attention that is close to being simultaneously inward and outward focused, thereby making one more conscious of the interrelatedness of phenomena. The earliest tracings of open awareness appear to stem from Buddhist origins (Gunaratana, 1996) and it was possibly first introduced in the West through the teachings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff in the early nineteen hundreds (Ouspensky, 1971). These days, aspects of open awareness have been integrated into some of the techniques of Neuro Linguistic Programming (Bandler & Grinder, 1976; Overdurf, 2013) and other psychological interventions, although it has received only nominal attention from the scientific community (E.G., Farb, et al. 2007, Hanson, 2011).

Opening the aperture of awareness

Open awareness involves the intentional observation of one’s thoughts, feelings and sensory perceptions in the present through opening the aperture of one’s awareness. This type of opening is facilitated by means of expanding one’s mode of perception to include the aspects of each unfolding experience that usually occur in or beyond the outskirts of conscious awareness and which are therefore usually unconscious or disregarded. In addition to identifying the subtleties of one’s internal experience, open awareness includes becoming receptive to the energetic and relational links between oneself and others and the environment. Depending on the individual and their reason for practising open awareness, the experience of self fluctuates and is therefore not an ultimate state, but rather one in which the individual experiences a felt sense of expansiveness and interconnection resulting from dis-identification from their limited self-concept. Open awareness is more than a technique, it is a natural mode of being, one that we, as humans, find ourselves in when we are completely free of burdens on every level – physical, mental, emotional and spiritual (Finlay 2013).

Escaping the trap of tunnel awareness

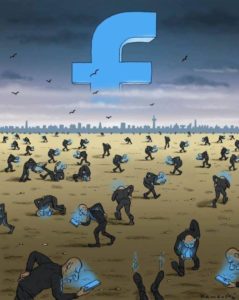

Research done by Olpin and Hesson (2015) suggests that stress is proliferating, with more people being negatively affected by it today than ever before. This points to the probability that we, as a society in general, are far from being free of burdens, which in turn may underlie why open awareness has become a largely forgotten trait or ability. Indeed, in an attempt to deal with the new or intensified types of challenges that the predominantly high-tech and fast paced lifestyles of today demand, we are, to a certain degree, being forced from open awareness into tunnel awareness in order to fulfil many of our functions in both the workforce and in our social life. A potential resulting effect on us as a collective may be that we have become tuned out of what was, in past times, a more common state for us, in exchange for being tuned in to the devices that many believe make life convenient in this era. Society has never before had the technological means to capture and narrow our attention as it does today. With our online digital devices readily on hand, the media and the medium have merged, and the result is, to some extent, we have become the victims of attention slavery, giving rise to a generation of digital zombies (Spitzer, 2016).

Research done by Olpin and Hesson (2015) suggests that stress is proliferating, with more people being negatively affected by it today than ever before. This points to the probability that we, as a society in general, are far from being free of burdens, which in turn may underlie why open awareness has become a largely forgotten trait or ability. Indeed, in an attempt to deal with the new or intensified types of challenges that the predominantly high-tech and fast paced lifestyles of today demand, we are, to a certain degree, being forced from open awareness into tunnel awareness in order to fulfil many of our functions in both the workforce and in our social life. A potential resulting effect on us as a collective may be that we have become tuned out of what was, in past times, a more common state for us, in exchange for being tuned in to the devices that many believe make life convenient in this era. Society has never before had the technological means to capture and narrow our attention as it does today. With our online digital devices readily on hand, the media and the medium have merged, and the result is, to some extent, we have become the victims of attention slavery, giving rise to a generation of digital zombies (Spitzer, 2016).

A digital zombie can be described as a person using digital technology to a point that they become fixated in an artificial reality. Psychiatrist and neuroscientist Manfred Spitzer (2016) argues that digital zombies have difficulty looking people in the eye or carrying on healthy conversations. They are less aware of life happening around them (classic tunnel awareness) and they have limited social skills in the real world. Furthermore, they are prone to an early onset dementia, known as digital dementia (Spitzer, 2016). Generational research has shown that the more time we spend looking at screens, the more likely we are to experience psychological distress and depression (Twenge, 2017). Excessive use of mobile digital devices (including smartphones) can potentially hard-wire tunnel awareness in children and adults, with detrimental consequences regarding health, learning and attention disorders, performance issues, relationship conflicts and social problems (Spitzer, 2016, Twenge, 2017). Tunnel awareness may be an underlying cause of the sense of separateness between individuals, religions, ethnic groups, etc. It narrows our perceptions and capacity to think, feel and behave holistically.

With our attention locked in by the gadgets (predominantly smart phones) that we have become accustomed to use in order to operate in this world, we may find ourselves unable or less able to release our attention, when appropriate, in order to interact with each other and our environment in an ethical and effective manner. The result on individuals may be a rise in specific social and relational problems, as well as elevated stress levels, which, if unresolved can lead to burnout (Brühlmann, 2011; Cartwright & Cooper, 1996). This phenomenon may in turn further convince one to retreat into a virtual world and to favour interacting with virtual ‘friends’ for the sake of convenience, quick fixes and immediate gratification (Twenge, 2017). This hypothesis suggests that as an increasing amount of the world’s human population becomes more tuned into a virtual reality, our ability to tune back out into the rest of reality may become jeopardised. In a mode of tunnel awareness, one may be less able to think creatively and deal with life’s stressors resourcefully (Farb, et al. 2007; Finlay 2013; Hanson & Mendius, 2009; Overdurf, 2013; Rossi, 1993; Ouspensky, 1971). On the other hand, if one is able to counteract such a narrowing of awareness, through applying a means to reopen one’s mode of perception, then the person may find that he or she is better equipped to navigate the multi-dimensional challenges of life beyond the flat screens of our electronic devices.

Open awareness to the rescue

Open awareness has been found to counteract stress, anxiety and a sense of separateness, by activating a calm and resourceful state that is accompanied by a sense of interconnectedness (Yates, 2015, Dangeli, 2020, Hanson & Mendius, 2009).

Through using and teaching open awareness techniques since 2004, as well as studying the phenomenology of open awareness in my 2015 MSc research, I have found that shifting out of tunnel awareness into open awareness can be achieved with relative ease by children and adults of at least moderate physical and psychological health. By introducing open awareness skills in learning environments and in the work place, the harmful effects of tunnel awareness can be prevented, and mindful resourcefulness can be promoted.

Embodying open awareness

In order for open awareness to be reliably available and effective in stressful situations, it needs to become embodied through regular practice. There are a variety of practices available today, many of which can be learned in a short amount of time. I’ve been practising judo since the age of five. During the nineties I began combining basic judo movements with yoga and qigong. Eventually a distinct practice that I refer to as jumi (judo mind) was established. The core objective of jumi is to develop and embody open awareness. While jumi serves as a mind-body practice by itself, it can also be used to compliment other integral practices. There are jumi sequences suitable from young to old, at any level of fitness and psycho-spiritual development. These days I readily recommend jumi practice to my clients, and they consistently report positive results.

Conclusion

Open awareness (OA) is a mindful mode of perception accompanied by a calm, receptive and resourceful state.

-

OA cultivates metacognitive introspective awareness – in which the mind can observe its own state and activities – an awareness of the mind itself.

-

OA enhances extrospective awareness – sensory perceptions and somatic experience.

-

OA reframes one’s current experience of self, placing phenomena within one’s awareness, as opposed to these being experienced separate from oneself. This reduces distress, enhances intuition and promotes a sense of interconnection.

-

OA can be easily learned and applied in all contexts. Jumi practice is recommend for embodying OA.

The Open Awareness Handbook (free download)

The Open Awareness Hub

Jumi website

References

Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1976). The Structure of Magic, Vol. 1. Science and Behaviour Books, Palo Alto.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Brühlmann, T. (2011). Open Forum at The World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Retrieved April 4, 2013, from the World Wide Web: http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=77Fy7kKHAfA

Cartwright, S. and Cooper, C.L. (1996). ‘Coping in occupational settings’, in Zeidner, M. and Endler, N.S. (Eds.), Handbook of Coping, New York: Wiley, pp. 202–20.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S., Capuano, T., Baker, D., & Shapiro, S. (2005). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout. Holistic Nursing Practice, 18(6), 303–308.

Dängeli, J. (2020). Exploring the phenomenon of open awareness and its effects on stress and burnout. Consciousness, Spirituality & Transpersonal Psychology, 1, 76-91. https://www.journal.aleftrust.org/index.php/cstp/article/view/9

Farb, N.A.S., Segal, Z.V., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., Fatima, Z., and Anderson, A.K. (2007). Attending to the present: Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reflection. SCAN, 2, 313-322.

Gunaratana, B. H. (1996). Mindfulness in Plain English: Revised and Expanded Edition, Wisdom Publications. Retrieved October 2014, from The World Wide Web: http://www.vipassana.com/meditation/mindfulness_in_plain_english_15.php

Oplen, M. and Hesson, M. (2015). Stress Management for Life: A Research-Based Experiential Approach, 4th edition. Cengage Learning.

Ouspensky, P.D. (1971). The Fourth Way. Vintage; New edition

Overdurf, J. (personal communication, June 20, 2013) http://www.johnoverdurf.com

Spitzer, M. (2016). Digital dementia in the age of new media. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBopndZ4uhI

Twenge, J. (2017). Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/?utm_source=twb

Write, S. (2005). Burnout – A Spiritual Crisis. The Nursing Standard. vol. 19, no. 6

Yates, J. (2015). The Mind Illuminated. Dharma Treasure Press.